(Los Angeles Times)

Slip a fresh $20 bill under the bulletproof teller window of Donnie Anderson’s Medex marijuana dispensary on Century Boulevard — perhaps for a gram of cannabis or some THC-infused toffees — and the legal tender is transformed into something else: drug money.

Though the transaction is legal in California, under federal law that bill is not much different from the contents of a drug cartel’s safe — cash that most banks won’t touch.

So how is Anderson supposed to pay his employees, suppliers or business taxes? He deposits cash, in drips and drabs, into an account held by a limited liability company that his bank thinks is a property management firm.

“The bank doesn’t know what we do,” he said.

If this sounds like money laundering, you’re not far off.

Yet consider this: That same $20 exchanged at Canndescent, another cannabis company, takes a direct and transparent route into the financial system.

When the marijuana cultivator sells its product to a dispensary, one armored car drops off the pot and another picks up the cash payment — and then heads to a downtown Los Angeles branch of the Federal Reserve Bank.

There the cash is deposited into the account of a local credit union, one that’s eager to do business with Canndescent.

Tom DiGiovanni, chief financial officer of Canndescent, at the cannabis company’s cultivation site in Desert Hot Springs.

“After all the horror stories I’ve heard, it does seem like a little bit of magic,” said Tom DiGiovanni, Canndescent’s chief financial officer.

Indeed, though the same laws apply to Anderson’s dispensary and Canndescent’s Desert Hot Springs farm, the world of cannabis banking is so full of contradictions that one business can truck money to a federal facility while the other is left to play a high-stakes game of hide-and-seek with its cash.

“It’s the early stages of the Wild West,” said California Treasurer John Chiang, who is leading an effort to reform cannabis banking, a problem dating back to 1996 when California legalized medical marijuana.

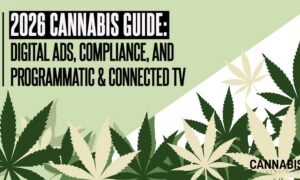

With recreational use set to become legal next year under Proposition 64, cannabis sales in the state are expected to top $7.5 billion in 2020, up from about $3.3 billion last year, according to data provider New Frontier and cannabis investor network Arcview Group.

But while Proposition 64 broadened the legal use of pot, it did nothing to relax banking regulations.

“It left significant questions unresolved,” Chiang said. “How do you handle the taxation of cannabis dollars and the banking of billions of dollars of transactions that are going to take place here in California?”

Last year, Chiang created a group of cannabis and banking industry trade groups, attorneys, regulators and others, trying to figure out how to bring the cannabis industry into the financial mainstream. But it’s a vexing challenge, and one that cannot be solved by the state alone.

Marijuana is legal for medical use in 29 states and for recreational use in eight, yet the federal Controlled Substances Act lists it alongside heroin and LSD as both dangerous and having no accepted medical use.

And for banks, federal laws are paramount.

Banks and credit unions can guarantee deposits because they have federal deposit insurance. They rely on Federal Reserve systems to make wire transfers, handle electronic payments and process checks. And they all answer to at least one federal regulator.

Banks and credit unions also are required to tell federal authorities if they suspect that their customers might be engaged in illegal activity. And when it comes to following those rules, the stakes are high.

“The FDIC could step in and shut down a bank, and it can do that with very little notice,” said Julie Hill, a law professor at the University of Alabama and former finance industry attorney who has studied cannabis banking. “Nobody’s ever gotten their bank brought back to life after it’s been closed by regulators.”

Because of that, many banks won’t even take the risk.

“From a federal level, it’s illegal,” Jim Brush, chief executive of Summit State Bank in Santa Rosa, told Chiang’s working group in May. “It really doesn’t matter what California does.”

Still, federal officials have cracked open the door for banks and credit unions.

In 2013, the Justice Department said it would focus its marijuana-enforcement efforts on preventing sales to minors, interstate trafficking and a handful of other crimes.

The following year, the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, or FinCEN, part of the U.S. Treasury Department, released guidelines for financial institutions that want to work with marijuana companies. They require additional reporting and demand that banks monitor companies for activities that remain Justice Department priorities.

FinCEN reported that 368 banks and credit unions were serving the industry in March, up from fewer than 300 at the beginning of 2016. But that’s a tiny fraction of the nation’s nearly 12,000 banks and credit unions.

Hill said so few institutions are playing along because FinCEN’s guidelines don’t offer clear legal protection. And some banks don’t want to be in the uncomfortable position of policing cannabis companies.

“How would you know a business isn’t selling to minors unless you’re in the store all the time?” Hill said.

What’s more, with a new administration in the White House and avowed marijuana opponent Jeff Sessions running the Justice Department, it’s not clear whether the the feds will take a harder line on pot.

With many cannabis companies unable to get bank accounts, they are often left to deal in cash, which is inconvenient and dangerous.

Take Jerred Kiloh, owner of Higher Path Collective. His Sherman Oaks dispensary had sales of about $4 million last year, so he owed more than $200,000 in taxes to Los Angeles alone, he told Chiang’s group.

Imagine, Kiloh said, carrying that much cash.

“Right now, at the downtown office of finance, there’s a six-story parking structure 500 yards away,” he said. “I have to walk through what is essentially a homeless encampment with a duffel bag full of cash, walk across the street, go through security and then sometimes stand in line.”

Kyle Kazan, a former Torrance police officer who runs a firm that invests in cannabis growers and retailers, said the lack of access to banking poses big safety risks.

“Real lives are in danger because there’s so much cash in play here,” Kazan said.

In one infamous case from 2012, an Orange County dispensary owner was kidnapped, tortured and had his penis cut off by assailants who thought that the businessman was burying cash in the desert outside Palm Springs.

Burying cash might seem ridiculous in the 21st century, but it’s not unheard of in the cannabis industry.

“We get lots of cash, and sometimes it has been washed — actually washed — because it had been buried out in the backyard,” said John Bartholomew, treasurer-tax collector for marijuana-rich Humboldt County, speaking to Chiang’s group last year.

Cash payments are a hassle for governments too. Todd Bouey, L.A.’s assistant director of finance, told Chiang’s group that the city had to buy new currency-counting machines because office workers were spending so much time counting and recounting cash tax payments from marijuana businesses.

“No one comes in with the type of cash they come in with,” Bouey said. “ It was taking hours to get through one deposit.”

Still, Bouey said that only about 20% of marijuana businesses that pay taxes are doing so in cash. Most pay with checks, indicating that they have bank accounts — either openly or on the sly.

Even though they are few, and mostly small, there are banks and credit unions that are hungry for customers and willing to quietly open accounts for cannabis businesses.

The Los Angeles-area credit union serving Canndescent has been losing traditional members, and hopes that by serving young, growing companies in a booming industry, it will be able to offer checking accounts, home loans and auto loans to the companies’ employees.

“We’ll probably max out at about 200 businesses, and we’re basically at capacity,” said an executive, who provided details of the institution’s cannabis banking operations on the condition that neither his name nor the institution’s be used. “ I don’t need to get inundated with phone calls.”

Finding a willing institution is just the first challenge. Next, companies have to qualify for an account — and be able to afford it.

At the credit union, cannabis companies have to pay an upfront fee of as much as $10,000 to cover the cost of independent financial audits and criminal background checks for the owners.

The credit union also charges recurring fees to cover the cost of ongoing due diligence and reporting required by FinCEN. For growers, the credit union charges $5,000 a month. For dispensaries, it’s $7,500.

“We’re verifying that they’re not breaking any laws, not evading taxes, not doing anything that could be a legal or ethical violation,” the executive said. “We assume we’re going to be investigated at some point by our regulators and maybe by the IRS or the DEA.”

Companies also have to hire the armored car services to take their cash directly to a Federal Reserve Bank branch. “We don’t want cash coming to the credit union,” the executive said. “If we did, then we’d have people signing up to rob the place.”

Other businesses that handle lots of cash, such as big-box stores, often have their cash sent directly to the Federal Reserve.

Matthew Schiffgens, a spokesman for the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, said in an email that it’s no different for marijuana businesses — with the understanding that the credit union must make sure that its clients are following FinCEN guidelines and other rules.

The National Credit Union Administration, the industry’s insurer and chief regulator, also has taken an agnostic approach to cannabis, telling credit unions to proceed with caution.

“We’ve said, look, this is your business decision,” spokesman John Fairbanks said. “We expect you are going to analyze the risks of doing business with these companies and take prudent and necessary steps to mitigate that risk.”

To that end, the L.A.-area credit union is not making loans to cannabis businesses. It’s easy for the credit union to close down a checking account if it thinks that a business is breaking the rules, but unwinding a loan could be trickier. And if federal authorities go after a business and seize its assets, the credit union might be unable to collect.

Despite the high fees, plenty of companies are signing up for accounts.

Dan Grace, chief executive of Dark Heart Nursery in Oakland, which supplies cannabis plants to dispensaries and commercial growers, figures that two of his company’s 50 employees spend all their time on cash management. He said a bank account that would cost him $60,000 a year in fees would more than pay for itself.

“When we have employees handling so much cash, we have to have lots of checks and balances,” said Grace, who is not one of the credit union’s clients.

Others, though, balk at the price. Anderson said there’s no way it would make sense to pay $7,500 a month for a checking account for his dispensary.

“They’re trying to rob the industry,” he said. “They all look at us like cash cows. I’d rather take my chances and do what we’ve been doing.”

Chiang’s working group has focused largely on the problems faced by cannabis businesses because of shaky access to banking, but is now turning to potential solutions.

Hezekiah Allen, executive director of the California Growers Assn. and a working group member, said one idea that’s caught his interest is the creation of a “bankers bank” — some kind of private entity that could do upfront due diligence and compliance work.

“Our members would go through a week or 10-day-long screening process and, if they meet the requirements, they’d be able to open an account with one of a dozen banks,” Allen said.

Nicole Howell Neubert, an attorney who works with cannabis businesses and a member of Chiang’s group, said at this point she hopes that the state can simply find a way to make a few more banks and credit unions feel more comfortable.

“Ultimately, it requires a federal fix to address the issue,” she said. “But I think there will be some enterprising, smaller financial institutions that will see this as an opportunity and, I hope, move forward.”